Updated June 7, 2024

Diagnosis requires thorough clinical, surgical and pathologic assessment. See Figure 2 (link to Theresa’s flow chart for diagnosis)

- Complete history and physical, including pelvic and pelvic-rectal examinations

- CBC, BUN, Cr

- Tumor markers: CA125 and CEA in all patients. CA19-9 and CA15-3 are associated with breast and gastrointestinal tract cancers; however, they may also be elevated in clear cell carcinomas, endometrioid carcinomas and dermoid cysts (CA19-9).

- AFP, HCG (quantitative), LDH in patients under 40 (associated with germ cell tumours)

- Chest X-ray

- Imaging is informative. Pelvic ultrasound will help to determine level of suspicion (worrisome features include solid areas, increased vascular flow, bilaterality, ascites, excrescences, mural nodules etc.). CT chest/abdomen/pelvis with contrast is recommended for suspected stage III/IV disease or for suspected HGSC histology, to rule out peritoneal dissemination and for treatment planning and before referral to a gynecologic oncologist for consideration of surgery.

All patients presenting with suspected advanced staged ovarian cancer on imaging should be referred for subspecialist surgical care (Gynecologic Oncologists). Decisions regarding upfront surgery to achieve optimal debulking vs. pre-operative chemotherapy if optimal debulking is not possible or is not medically appropriate should be made in a multidisciplinary team setting.

Surgery provides staging and prognostic information, and it may be therapeutic through the removal of diverse clonal populations. Surgical expertise, specifically surgery by a gynecologic oncologist, has been demonstrated to improve the survival of patients with EOCs. Centres with a high volume of surgical procedures for EOC have better outcomes. If malignancy is suspected, surgery should be performed by a gynecologic oncologist with the intent of optimal debulking.

Successful treatment of EOC often begins with surgical management, including surgical cancer staging for apparent early disease, and tumour debulking for advanced stage disease. Staging procedures have changed over the last decade with an appreciation of i) differences in disease distribution and clinical course according to the histotype, and ii) recognition that fertility sparing staging procedures can be appropriate in some situations. Core components of staging usually include removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries (BSO), removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), omentectomy, directed biopsies, washings, +/- assessment of retroperitoneal lymph nodes (pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy).

Careful review can enable triage of suspected benign adnexal lesions to General Gynecologists and suspicious or indeterminate lesions to Gynecologic Oncologists so that one optimal surgical procedure can be performed. Even in the situation of confirmed malignancy, careful consideration needs to be given to patient wishes, medical urgency, the surgical approach, the possibility of achieving optimal surgical debulking (vs. pre-operative chemotherapy), chemo-responsiveness of the disease, and medical comorbidities of the patient.

The 3 most important clinical prognostic factors influencing outcome of EOC are stage, tumour grade and the presence or absence of visible residual disease at the completion of initial surgery. In apparent early-stage ovarian cancer, complete staging with multiple biopsies and possibly lymphadenectomy is key to ruling out microscopically advanced disease. Fertility sparing surgery in young women may be acceptable with specific histotypes (such as endometrioid carcinoma, LGSC, and borderline tumors) when the contralateral ovary and uterus are uninvolved.

Classification Criteria (FIGO) for Epithelial Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Primary Peritoneal Cancers is as follows and accessible through FIGO, SGO, and other websites:

Table 1: FIGO (2014) and TNM staging

Other considerations are as follows:

- Histologic type including grading should be designated at staging;

- Primary site (ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum) should be designated where possible;

- Tumours that may otherwise qualify for stage I but involved with dense adhesions justify upgrading to stage II if tumour cells are histologically proven to be present in the adhesions.

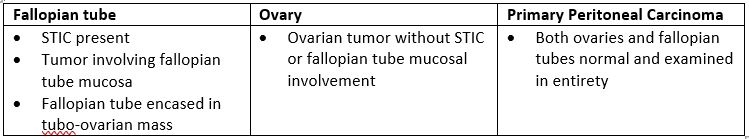

Of note, staging for primary fallopian tube and primary peritoneal carcinomas of high-grade serous type is similar. Indeed, modern pathology criteria now consider ovarian serous, primary peritoneal, fallopian tube serous carcinomas as encompassed by pelvic (non-uterine) serous carcinoma. Table 1 summarizes the criteria for assignment of primary tumor site.

Table 2: Criteria for designation of primary tumour site in high-grade serous carcinoma

When patients present with apparent advanced stage disease, decisions regarding upfront surgery to achieve optimal debulking vs. pre-operative chemotherapy (if optimal debulking is not possible or is not medically appropriate) are made within a multidisciplinary team. This approach is also reflected in existing cancer management guidelines [21]. Randomized clinical trials demonstrate that clinical outcomes for patients treated by upfront surgery, or by pre-operative chemotherapy followed by surgery are the same [22, 23]. Pre-operative chemotherapy is associated with slightly lower rates of operative complications, higher rates of optimal debulking, and reduced rates of bowel resection [24]. In some cases, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be required to decide whether primary surgery or pre-operative chemotherapy is the best initial strategy, based on distribution and volume of disease.

A core biopsy is the gold-standard diagnostic sample required to establish the disease histology and is required for biomarker testing and treatment planning in patients with advanced stage disease (spread to lymph nodes, peritoneal or pleural spaces or visceral organs).

If the multidisciplinary decision is made to start with pre-operative chemotherapy, a histologic diagnosis, usually by core biopsy (or sometimes by surgical/laparoscopic biopsy), is required. The biopsy is also used for additional molecular testing to guide treatment decisions (see section 3.6).

If a pre-treatment biopsy cannot be obtained, or is not technically successful, consideration can be given to upfront surgery or a laparoscopic biopsy. Cytologic evaluation of fluids (ascites or peritoneal effusions) is considered the least desirable option, but in rare cases cytology can be used. Cell blocks, embedded in FFPE are recommended for better characterization and to facilitate additional testing (see section 3). If a histologic sample cannot be obtained, cytologic evaluation can be accepted, but is considered the less desired option. To differentiate from colorectal cancers, a serum CA125:CEA >25 helps to support the diagnosis of a primary ovarian/primary peritoneal/fallopian tube cancer[25] , but does not help to determine the disease histotype. Care should be taken to rule out other primary cancers. For any patient in whom the response to chemotherapy is poor, pathology should be scrutinized/reconsidered. Low-grade diseases such as low-grade serous carcinoma are unlikely to respond well to chemotherapy and will more likely benefit from surgical debulking (underscoring the value of a good histologic diagnosis, as cytology can seldom discriminate between high and low grade serous ovarian cancers).

The standard of care in cancer therapy often includes biomarker testing on tumour tissue. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers are used to counsel patients and plan management. Biomarker expression can also determine eligibility for clinical trials.

A histologic sample is the gold-standard diagnostic material required (e.g., surgical sample or a core biopsy) to make an accurate diagnosis, and to complete all additional biomarker testing.

BRCA1/2 tumour testing is now standard of care for all high-grade EOCs (i.e., high-grade serous, high-grade endometrial, carcinosarcomas, high-grade adenocarcinoma NOS) [26]. This identifies patients with somatic/tumour BRCA mutations and for those with advanced disease (stage III/IV) the finding inform decisions around maintenance treatment following the completion of surgery and first-line chemotherapy. Patients with BRCA1/2 tumour mutations are more likely to harbor germline mutations. All patients with non-mucinous EOC, regardless of tumour testing results, should undergo germline hereditary cancer testing – see section 15. Hereditary Cancer Syndromes).

Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) is present in approximately 50% of high grade serous EOCs. Tumour HRD status may determine prognosis and be used for decision making about maintenance therapy after the completion of surgery and chemotherapy (see section 4.3 Maintenance Therapy). Presently, HRD testing is not funded or available in BC. HRD testing may be accessed through private laboratories (patient self-pay) or occasionally through access programs.

For women of childbearing potential, where fertility preservation may be desired, review with a Gynecologic Oncologist is required. An urgent referral to a fertility clinic should be arranged. For most high-grade EOCs, or those with advanced stage disease, fertility-preservation is not usually recommended as optimal cancer management involves removal of all reproductive organs. Some low-grade and early-stage cancers may have the option of fertility preservation (e.g., low grade endometrioid and low grade mucinous). This surgery would involve removal of the affected ovary and fallopian tube, as well as peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, and omental biopsy, while preserving the contralateral ovary and the uterus. This strategy requires careful discussion of the potential risks such as under-staging and cancer recurrence or development of a new cancer in the remaining ovary or in the uterus. These must be weighed against the odds of successful future pregnancy. Sampling of the endometrium should be considered if a hysterectomy is not being performed. Birth control methods should always be used if fertility is/may be intact.

- In the reproductive age group, extensive pelvic endometriosis can mimic the findings of pelvic malignancy and present a diagnostic challenge.

- In the postmenopausal age group, diverticular disease can mimic ovarian cancer.

- Patients under 40 with suspected cancer are more likely to have germ cell cancers and initial conservative surgery only is needed (e.g., unilateral BSO). Therefore, preoperative b-HCG, AFP, and LDH are of immense value. When the diagnosis is uncertain, conservative surgery is appropriate.

- The objective is to remove tumour masses intact without rupture or spill to avoid the potential for spread of malignant cells. It is recognized that endometrioid and clear cell cancers, which arise in association with endometriosis, are prone to rupture. The impact of intraoperative rupture on prognosis is controversial. No additional treatment is usually recommended for patients with intraoperatively ruptured stage I cancers. If the tumor can be removed intact with the use of endobags, when the procedure is done laparoscopically, this may be appropriate.

- Aspiration of pelvic masses preoperatively is NOT recommended for diagnosis. The aspiration of intracystic fluid seldom gives the diagnosis and may compromise prognosis if rupture occurs prior to surgery. Unlike intraoperative rupture, preoperative rupture appears to be associated with a worse outcome and may influence treatment and prognosis.

- In stage I ovarian cancer, once the diagnosis of malignancy has been made, a thorough staging procedure should be performed. Peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsies, pelvic and para-aortic node assessment, and omentectomy are all important in determining the presence of subclinical extra-ovarian spread. Wedge biopsy of the contralateral ovary is not required if the ovary is clinically normal as this may further compromise fertility.

- The objective of surgery is to reduce the residual disease to no macroscopic disease/R0 (maximal cytoreduction). Although patients with residual disease < 1 cm (R1) are considered “optimally debulked” the greatest benefit is seen in those with R0 at completion of surgery [19].

21. Wright AA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer: Society of Gynecologic Oncology and American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Oct;143(1):3-15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.022. Epub 2016 Aug 8. PMID: 27650684; PMCID: PMC5413203.

22. Kehoe, S., et al., Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet, 2015. 386(9990): p. 249-57.

23. Vergote, I., et al., Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med, 2010. 363(10): p. 943-53.

24. Bartels at al. A meta-analysis of morbidity and mortality in primary cytoreductive surgery compared to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian malignancy, Gynecologic Oncology, Volume 154, Issue 3, 2019, Pages 622-630,

25. Yedema, C.A., et al., Use of serum tumor markers in the differential diagnosis between ovarian and colorectal adenocarcinomas. Tumour Biol, 1992. 13(1-2): p. 18-26.

26. Mosele MF et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol. 2024 Jul;35(7):588-606. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.04.005. Epub 2024 May 27. PMID: 38834388.